The Alipore Post x DAG

A peek into DAG's ongoing exhibition and publication 'The Babu and the Bazaar'

Dear readers,

As many of you may know, I was born and raised in Alipore, Calcutta. While the cityscape may have morphed over the years, there is still a strong sense of history every time I visit home. One of the most fascinating parts of living where I do is the proximity to Kalighat, famous for the Kali temple and the amazing craftspeople who make the traditional Kalighat pats, sandesh moulds and shola pith artefacts.

I recently came across a stunning showcase by DAG, which reflects the new-age aesthetic of modern India: The Babu and the Bazaar, a gorgeous amalgamation of the old and the new, of tradition and modernity, with rare artworks from 19th and early 20th century Bengal. Curated by historian and scholar Aditi Nath Sarkar, the exhibition and its accompanying publication by Sarkar and Shatadeep Maitra, attempts to unravel part of Calcutta's history, culture, class biases and gendered hierarchies and emerging art practices through rare artworks over a 100 years old.

What draws me to the works is the richness of the iconography and the depiction of women in the different mediums and the varying levels of detailing, as you’ll see in this newsletter.

A walk down memory lane

“In the 19th century, Calcutta was at the crossroads of tradition and modernity. Originally a township made up of a cluster of three or four villages at the end of the eighteenth century, the city was developing into a cosmopolis at a rapid pace. As the city thrived, its art and culture developed. Square pat paintings, now better known as Kalighat pats because they were found around the landmark temple by Mukul Dey in the 1930s, were sold by patua artists across the city.

The land-owning and business-oriented babus and baniyas, who garnered great quantities of wealth, wanted their deities painted using the same oil paints and on cloth canvases, on which they had their portraits drawn by travelling European artists. Like elsewhere in the colonised world, printing presses were also seen in Bengal. Although initially introduced by Christian missionaries, local businesses dived into the printing industry and produced chapbooks (chotiboi in Bengali), which used engraved illustrations to entice readers.

The Babu & The Bazaar showcases the art of the 19th and 20th century Bengal art. Kalighat pats form the heart of the exhibition, designs of which were copied in great detail on commissioned oil painting as well as in popular prints (wood engravings, lithographs and oleographs at the end of the 19th century). Also on show are reverse-glass paintings, possibly Chinese in origin (specifically from Canton, present-day Guangzhou). The designs of the Kalighat watercolour paintings were copied and were meant to be sold in Calcutta—in turn showing just how popular the pats were. What makes the paintings unique are the stories and rituals they describe—a condensed summary of many pages of literary description, retold and warped innumerable times, over hundreds of years.”

-from the book The Babu and the Bazaar by Aditi Nath Sarkar and Shatadeep Maitra

Art Appreciation

Calcutta, my dear City of Joy, is like a long love poem. Let us celebrate the imagery from over 100 years ago through a world of unique depictions and styles:

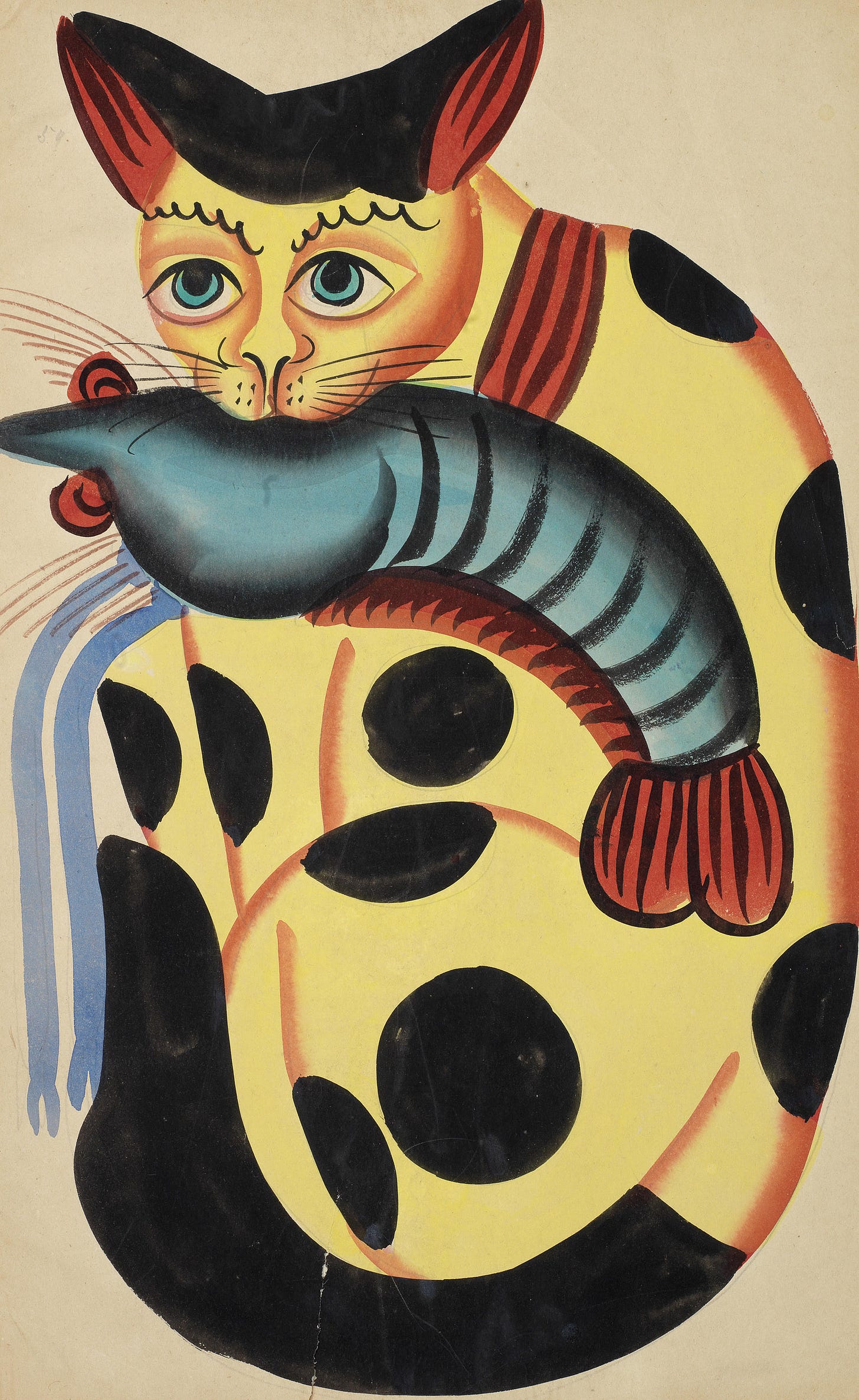

Reverse-glass art was originally introduced to the Indian subcontinent in the 19th century by Chinese or Parsi traders along the Western coast, but their popularity spread in the next 100 years. This selection of glass paintings was plausibly made in Canton (present-day Guangzhou) and brought to India as peddling merchandise in the 19th century. The artists responsible for these images remain unknown, but their presence shows a unique confluence between two vastly different cultures.

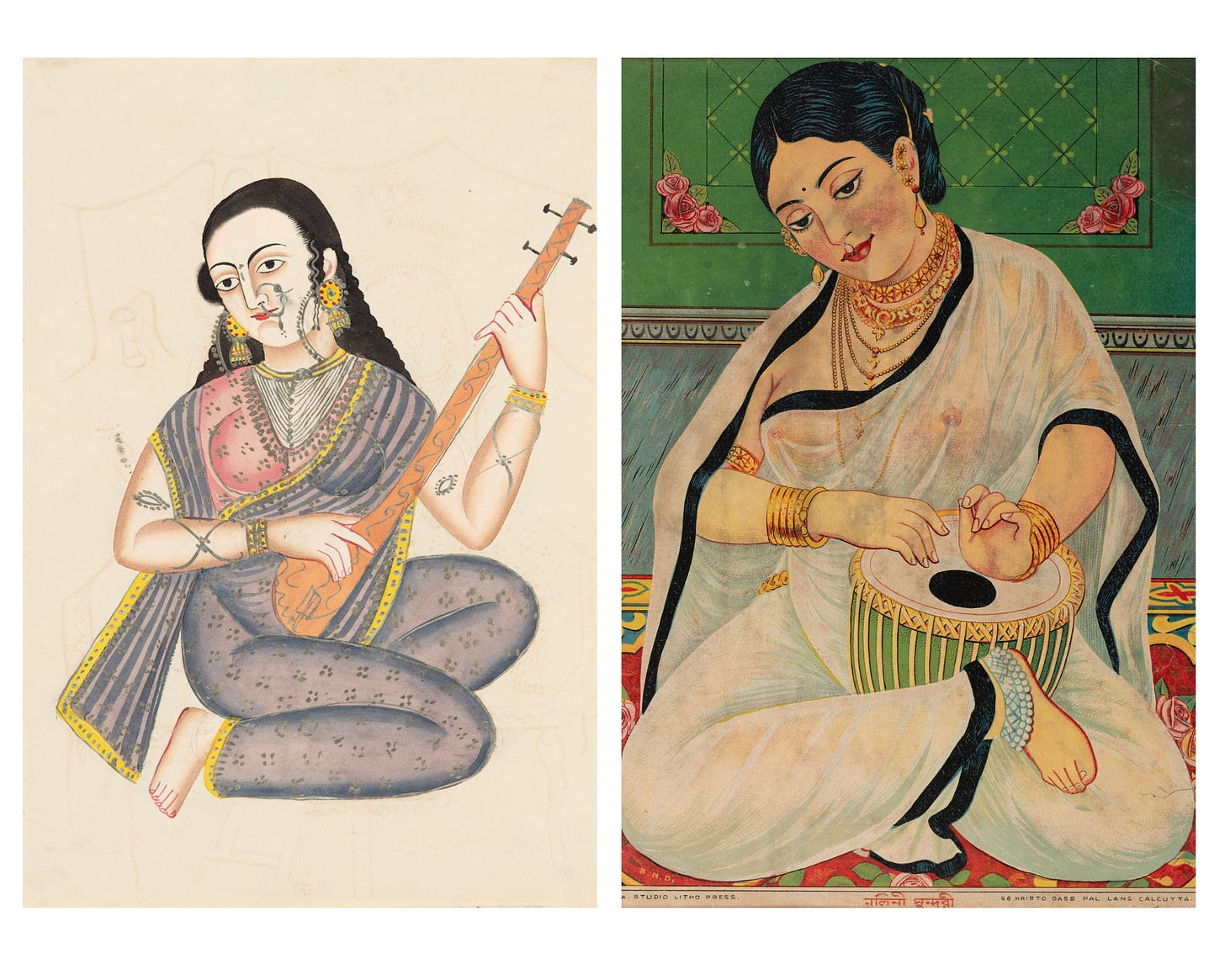

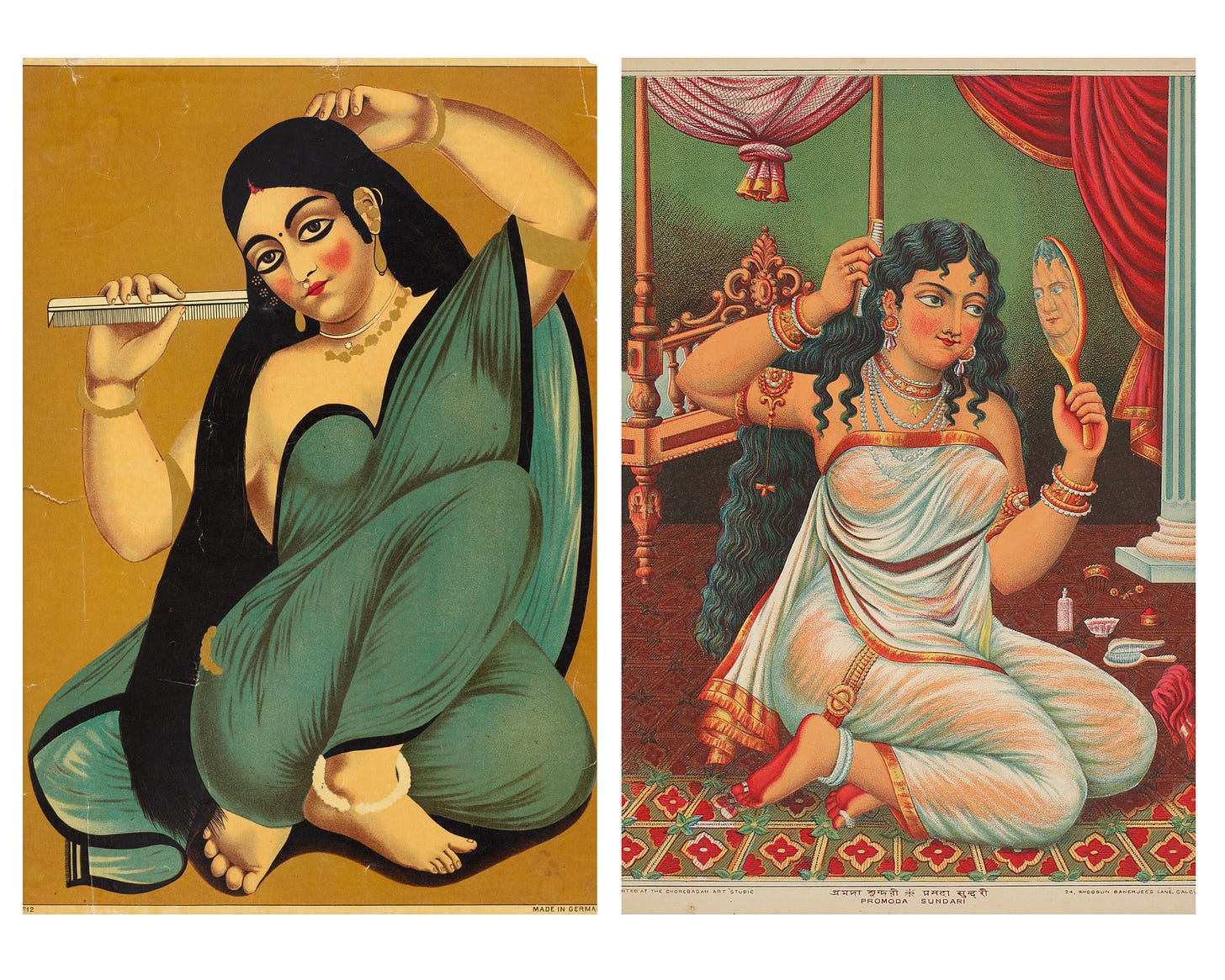

It is not difficult to imagine that among secular prints, pin-up style art sold in the highest numbers. Reverend James Long’s documentation of the Bat-tala presses that printed erotic literature was highly popular by the middle of the 19th century to such an extent that the colonial government tried to legally ban their production. The Sundari images describe complex social ideas and innuendos with hidden implications of women during that time.

Fun fact: The Bengali typeface was first used in Nathaniel Brassey Halhead’s Grammar of the Bengal Language, published in 1778.

The image of a cat stealing a prawn or fish has been made popular through the paintings of Jamini Roy—one of the earliest modern artists from Bengal—but the iconography dates back to the days of Kalighat pats. A metaphor for corruption amongst the elite as well as religious heads, the imagery is intended to evoke satirical humour. Belonging probably to a later period, the work underlines the deterioration of the Kalighat tradition; not only did the artist paint the feline with unnatural round patches, but also mistakenly extended the right arm further from where it should have been.

In the 19th century in Calcutta, widows who survived sati were commonly abandoned by their families, and many became sex workers to earn a livelihood. The woman in the paintings, who wears the widow’s white and black saree, had suffered the same fate.

Art in Contrast

One of the most interesting aspects that stood out for me at the show was the contrast between the commissioned oil paintings and mass-produced prints and the watercolour Kalighat pats, and note the stylistic differences between the various artistic traditions that emerged in the city:

After the turn of the twentieth century, the tangent of art prints changed drastically. A division was drawn between what was considered ‘printing’ and what was ‘printmaking’. Printmaking was thought of as an artistic exercise with an individual printmaker producing a limited number of editions by hand from a print-matrix at the studio. Printing was relegated to a commercial activity of mass-production at a printing press.

The Sundaris (beautiful women) became popularly available in Calcutta in the last decades of the 19th century. These erotic pats introduced a voyeuristic gaze to Bengal art by showing women inside their sanctum sanctorum.

If you’re in New Delhi and visit the exhibition, do look out for these contrasting depictions.

The exhibition is now open at DAG Janpath, New Delhi till 1st July, 2023, Monday through Saturday from 10.30am to 7pm. You can reach them here.

To order the publication at a 15% discount, use code ALIPORE (only for the first 25 orders) while writing to @dag.world on Instagram.

Wishing you a beautiful walk down the lanes of Calcutta,

Rohini

I love the flow in some of these paintings. Happiness is in the flow of all things. Thank you Rohini.

I really enjoyed reading this, plus of course the paintings!